So you’re you, yes? A person of conservative or traditional or simply unloony views walking your campus with your head in...

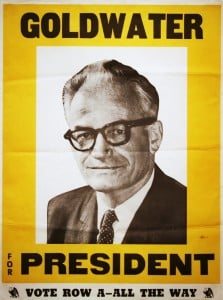

Why Goldwater Ran

The following is an excerpt from Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution (Regnery), now available in a new paperback edition. Barry Goldwater, an ardent and popular conservative, knew that, by 1963, the country was weary of liberal ideology, yet dismissed all suggestions that he run for president. One night, however, pressure from both public supporters and close friends forced him to reconsider: “Think of the thousands of young Republicans out there . . . think of the college students,” they implored.

Goldwater knew full well that the nation’s future and his own had been irrevocably altered. All the old doubts and insecurities about himself as a presidential candidate and president came flooding back. Jay Hall told Clif White that Goldwater was in a state approaching deep depression. Goldwater later admitted that he had told his wife Peggy that he would “definitely not seek the nomination.” Yet he made no formal announcement, letting the question of 1964 drift as long as possible, encouraged by the thirty-day moratorium on public politics that had been declared on November 22.

At last, at Kitchel’s insistence, he reluctantly agreed to talk things over with his closest friends and advisers. They met on December 8th in his Washington apartment. Present were Senators Norris Cotton of New Hampshire and Carl Curtis of Nebraska, former Senator William Knowland of California, Congressman John Rhodes of Arizona, Denny Kitchel, Bill Baroody, Peter O’Donnell, Jay Hall, Karl Hess, and John Grenier of Alabama, Southern field director for the draft committee.

Goldwater began by saying, “Our cause is lost,” and enumerated the reasons: (1) With Kennedy dead and Johnson the certain Democratic candidate, the battle would not be of issues but of innuendos and lies; (2) the notion of running against Johnson was abhorrent to him—LBJ was a wheeler-dealer, a hypocrite, a dirty fighter, a man who “never cleaned [the] crap off his boots”; and (3) no Republican could win in 1964 because Americans did not want three different presidents in one year.

Separately, but repeating the same theme like a Greek chorus, the conservatives seated around the room told Goldwater that he had no choice but to run. This was the conservative hour—it was now or never; the party needed him; Rockefeller, Nixon, Romney, Scranton, and Lodge were not the answer but the problem. They urged him to think of all of the sacrifices made by the National Draft Committee and other conservative groups, to consider above all “the hundreds of thousands of young Republicans out there, the Young Americans for Freedom, the college students, all the young people who came to hear you speak over the last decade.” He could not let them down.

The final speaker, by design, was Cotton. He compared Goldwater with Charles DeGaulle and described how the French general had brought about a renaissance of postwar France through his inspirational leadership. America now urgently needed new conservative leadership, the New Hampshire senator declared, that would change the nation carefully, reasonably, prudently. No one else in the Republican party had Goldwater’s “mass appeal—the vision, the character, the will to turn America in a conservative direction.” This was the hour, said Cotton—if Goldwater would give the command.

The heartfelt, eloquent appeal brought tears to the eyes of most in the room and left silence in its wake. They waited for Goldwater to respond, but he said nothing until at last he asked them to give him time “to sleep on it.” He thanked them for coming and asked Kitchel to remain. For a long time the two old friends sat silently, watching darkness fill the room, until at last Goldwater turned on a lamp and made a bourbon and water for Kitchel and a plain bourbon for himself. Pacing up and down, Goldwater recalled that he asked Kitchel, “What do you think?” to which his friend retorted, “What do you think?” Goldwater went over the same ground—the timing was wrong for a conservative Republican, the country would not accept a third president, the conservative cause could be badly hurt, he knew the kind of mean campaign Johnson would conduct. As he put it years later:

I wasn’t scared of a goddamned thing, but when you’re faced with the fact that black is black, you don’t try to change it to white. I knew that running against Johnson you’re running against all the controlled political organizations in the country. He was president, he built bridges, he built roads, and that’s the way you get elected.

Image by Cliff via Flickr.

Image by Cliff via Flickr.The two men sat silently, and then Kitchel, whom Goldwater trusted more than anyone else in the world because he knew that he would never mislead or lie to him, said bluntly, “Barry, I don’t think you can back down.” What was at stake, he went on, was not one man’s personal feelings, not winning or losing an election, but “the millions of conservatives around the country who had made a stand in favor of Barry Goldwater.” Goldwater admitted that he knew “the commitment—the bond I had made to so many conservatives and they to me—was virtually unbreakable at this point.” He almost blurted the fateful words:

“All right, damn it, I’ll do it.”

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism

Join a vibrant community of students and scholars

Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.

J.D. Vance on our Civilizational Crisis

J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....